Annual Letter on Philanthropy

Every year, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) kill nearly 40 million people. Seventeen million of those deaths occur before the age of 70: too many lives taken too soon. In fact, seven in ten of all deaths each year are the result of noncommunicable diseases, which also include strokes, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases. Add in injuries and the total represents more than three-quarters of all deaths annually. Many of these deaths are preventable, but the world’s governments—including the U.S.—have not made stopping them a priority.

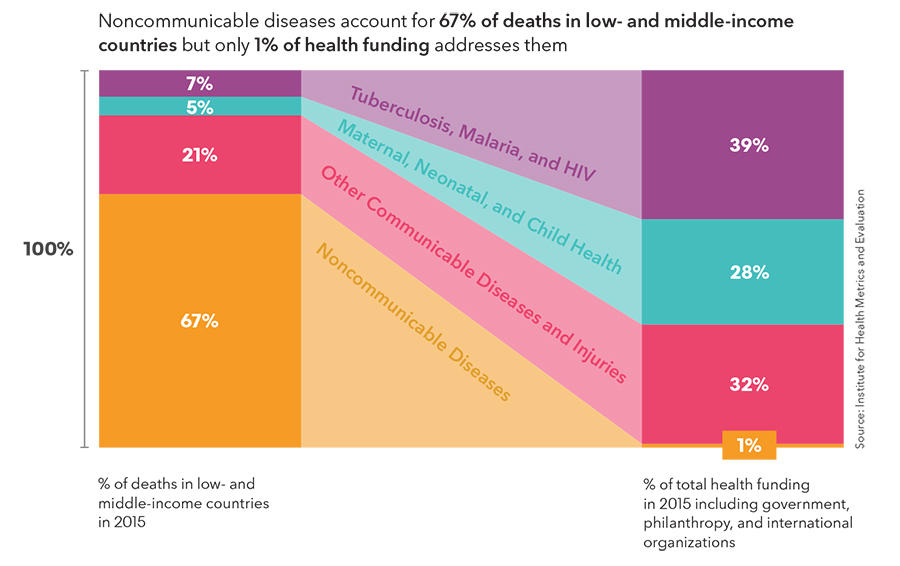

This problem is especially acute in low- and middle-income countries. As shown in the chart below, despite making up 67% of deaths in these countries, only 1% of global health funding is aimed at preventing noncommunicable diseases. As a global society, we lament NCDs, but we don’t do enough to stop them.

“We must go where the data leads us—and it leads directly to noncommunicable diseases and injuries.”

Michael R. Bloomberg

New vaccines and cures for communicable diseases are vitally important. I have invested $250 million to help eradicate both polio and malaria, following the lead of our friends at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. There are, however, too many needless deaths each year from NCDs—often simply because of a lack of awareness. Governments often fail to recognize that people are dying from causes that are preventable and that they can do a great deal to save those lives through smart policies and targeted funding. It is not a choice between fighting communicable diseases and preventing NCDs. We can do both— and philanthropy has an indispensable role to play in each.

To draw more attention to this challenge, I accepted an invitation from the World Health Organization (WHO) to become its first Global Ambassador for Noncommunicable Diseases. Battling NCDs has been a major focus of our work at Bloomberg Philanthropies for many years given our mission to ensure better, longer lives for the greatest number of people. To do that, we must go where the data leads us—and it leads directly to NCDs and injuries. My goal as a WHO ambassador is to raise awareness about these overlooked killers and get more governments to take stronger action to combat them.

The one NCD that does garner major attention and funding is cancer. That’s critically important as curing cancer would be a monumental victory for humanity. The U.S. government spends about $5 billion annually on cancer research. Last year, I gave $50 million to help establish a new institute for immunotherapy research at Johns Hopkins University. Immunotherapy seeks to use the body’s natural defenses, rather than radiation or chemotherapy, to destroy tumors. Recent studies indicate that a cure could finally be within reach. Private and public money devoted to cancer research is money well spent.

Heart disease, however, kills twice as many people (17.7 million) as cancer (8.8 million), with injuries not far behind (5 million). And, while searching to find cures for diseases is important, the truth is we need to do a better job of preventing them in the first place.

One reason for the lack of attention given to NCDs and injuries is that people, citizens and government officials alike, tend to blame the victims’ personal negligence or genetics. It’s true that our behavioral choices often lead to disease and injury and that genetics can predispose us to certain conditions. But that doesn’t mean the outcomes are inevitable. Far from it. We know that with every category of disease and injury governments can take modest actions to reduce the likelihood that their citizens will fall victim to them.

Fear of communicable diseases has led society to mount major campaigns to defeat them—and that’s excellent. But our casual acceptance of NCDs has led society to tolerate them at tragically high levels. None of us can escape death, but it’s time to change our view of it. Most of us can live longer, healthier lives if we take simple steps and demand that our governments adopt basic, and often inexpensive, protections.

At Bloomberg Philanthropies, we work with all levels of government around the world, but we concentrate our resources on cities, because local officials are in the best position to tackle our greatest challenges quickly and innovatively. Preventing NCDs is no different.

As a part of my role with the WHO, we are launching a new global network of cities, called the Partnership for Healthy Cities, aimed at implementing policies and interventions to prevent deaths caused by NCDs and injuries. From passing sugary beverage taxes and smoke-free laws to making sure that city streets are safe and walkable, there are many, often simple, policies that can have a big impact. We know this firsthand. During my time as mayor of New York City, one of our proudest achievements was helping to increase residents’ average life expectancy by three years, thanks, in part, to policies that put people’s health first. Through this new network, we are confident that by combining strong local leadership, seed funding, and technical expertise, we can help city governments around the world save lives.

Follow the Data

Raising public awareness about causes of death that otherwise receive little attention is essential. But sometimes the lack of awareness stems from a real problem: a lack of data. Incredibly, nearly two-thirds of all deaths in the world go unreported, and millions that do get reported lack a documented cause of death. How are elected officials and health care leaders to target their resources on the leading causes of death when they don’t have good data on what those causes are—or whether their interventions are working?

The truth is if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it. That is why we started our Data for Health program, co-funded by the Australian government. Data for Health is working with 19 countries—representing more than a billion people—to close the data gap on births and deaths. It’s our hope that the lessons we learn and the methods for collecting data that prove most effective will spread around the world and help governments better understand how to save more lives.

Tobacco Control

Tobacco is the classic example. The tobacco industry spent decades misleading the public about the dangers of smoking and fighting efforts to reduce it. When we proposed an indoor smoking ban in New York City, the industry went full tilt to defeat it. They lost, the ban proved highly effective and popular, and cities, states, and countries around the world have since adopted similar bans. Whether it’s smoking bans or tobacco taxes or regulations on packaging, the industry continues to fight any effort by governments to adopt policies that are proven to reduce use of their product—which is just about the only product sold legally that, if used as intended, will kill you about half the time.

One in ten of all deaths around the world is caused by smoking. Most take place in developing and middle-income countries where tobacco companies have shifted their marketing, lobbying, and legal efforts. With smoking on the decline in the U.S. and much of Europe, the industry is targeting the poor and using its deep pockets to bully governments from implementing life-saving public health measures.

We’re helping these governments stand up for their people through the Anti-Tobacco Trade Litigation Fund, which we created with the Gates Foundation. The fund supports governments like Uruguay, which last year successfully fended off a tobacco industry lawsuit arguing that its graphic package warnings ran afoul of international trade laws. The case was dismissed in 2016 by a World Bank tribunal, handing Uruguay a major victory and establishing a critical precedent.

Elsewhere, Romania passed a comprehensive tobacco control law; Shanghai and Shenzhen passed and implemented comprehensive smoke-free laws; the Philippines and Bangladesh began displaying new graphic tobacco packaging warnings; and Colombia and Ukraine both significantly raised tobacco taxes. It was not a good year for the tobacco industry.

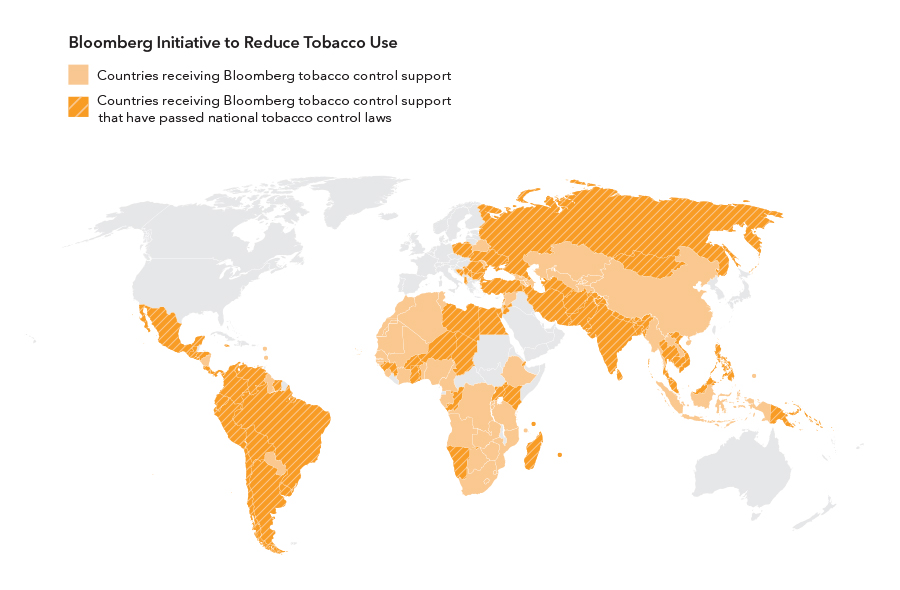

Since 2007, we have committed almost $1 billion to our tobacco control program and helped save 30 million lives. Back then, 11 countries had gone smoke-free. Today, the number stands at more than 50, covering nearly 1.5 billion people. This success demonstrates the important role philanthropy can play in spreading ideas that work.

Obesity Prevention

In addition to tobacco, one of the leading causes of noncommunicable disease is obesity. A common reaction to public health interventions aimed at combatting obesity is that government shouldn’t be involved, people should be allowed to make their own choices—and if they become obese and develop a disease as a result, that’s their fault. Leaving aside the fact that taxpayers bear a large burden for these diseases, a critically important role of government, I’ve always believed, is to help protect people from harm. That’s why we have laws requiring seat belt use. Those laws were controversial when they were first introduced. They’re not anymore.

People also have misperceptions around what causes obesity. They tend to think it’s primarily an issue of laziness—a lack of exercise. But that’s not true. The main culprit is diet. And the single biggest contributor to the problem is soda and other sugar-sweetened beverages, because they contain a lot of calories but consuming them doesn’t reduce your appetite. With no nutritional value, they are the definition of empty calories.

As awareness of the dangers posed by sugary drink consumption spreads, countries and cities have begun taking action. Two years ago, no municipalities had sugary beverage taxes. Now, seven cities and counties, representing more than eight million residents, have them. Last year, four large U.S. cities—Chicago (Cook County), Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Oakland—passed taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages. In each case, I backed efforts in support of these new laws. And, through grassroots organizing, these cities passed new taxes despite campaigns by the soda industry that outspent proponents at every turn.

More cities are likely to follow as the evidence in favor of the tax becomes increasingly irrefutable. In 2014, I supported an effort in Berkeley to become the first U.S. city to have a tax on sugarsweetened beverages. The law passed. And last month, a study showed that sugary beverage sales have declined by almost 10%—with more than a 15% increase in the sales of bottled water. A recent study of Mexico’s sugar-sweetened beverage tax found that purchases of taxed beverages have also declined by nearly 10%. In 2015, soft-drink companies mounted a concerted campaign to overturn the law, but thanks to the power of grassroots opposition, which we supported, they failed.

Road Safety

One area where we have made major gains against NCDs and injuries has been in vehicle crashes. But those gains have been limited to the U.S. and Europe—and they are now in danger: over the past two years, U.S. crash deaths have risen. Yet, as bad as the problem is here, it’s far worse in the rest of the world.

Vehicle crashes kill 1.3 million people each year and injure up to 50 million more. Crashes are the tenth leading cause of death in the world, and the number one cause of death for people aged 15 to 29. Once again, low- and middle-income countries suffer the most. Even though these countries have only half the world’s cars, they account for 90% of all road deaths.

One reason is that roads, walkways, and other infrastructure are not designed for safety. We are, however, working with governments and transportation experts to change that. Unsafe vehicles are also an important cause of crash deaths. In the U.S. and Europe, basic safety protections, like air bags and electronic stability control, are required by law. But in much of the rest of the world they are not, allowing automakers to sell cars that are virtual death traps. More than a century after Henry Ford began mass-producing cars, 80% of countries do not regulate vehicle safety standards.

In low- and middle-income countries, automakers—including U.S. and European manufacturers—routinely sell cars and other vehicles without many of the basic safety protections that are standard here at home. The result: an awful lot of people are being killed in crashes that they would have likely survived in the U.S. or Europe. This is especially disturbing because it costs so little to make cars safer, usually just a few hundred dollars. Yet hardly anyone is talking about this.

Our road safety program is beginning to change that through our work with consumer groups and governments. We have funded vehicle testing in Latin America, India, and Southeast Asia, and the results have been publicly released so that consumers can make more informed decisions. We have also begun conversations with manufacturers in the hopes of convincing them to make commitments to meet UN safety standards in every country, but we know that voluntary compliance is not enough. More governments must establish safety standards, and we have begun working with partners in countries to encourage them to take action.

The Work Ahead

Tobacco, sugary beverages, road crashes, and other NCDs and injuries are in desperate need of more attention and funding from both philanthropists and governments. The return on investment will be enormous, because many of the best solutions require relatively small sums—often to support grassroots organizing and advocacy campaigns.

There are philanthropists, elected officials, and leaders of non-governmental organizations who have made this life-saving work a top priority. But not enough. By encouraging everyone to do more, we can save millions of lives, spare millions more from pain and suffering, and create a safer, healthier, and happier world. It would be hard to find more inspiring and important work.

CEO Letter

Patricia E. Harris

Chief Executive Officer

In 2016, I visited Spartanburg, South Carolina, a textile town in the American South. Spartanburg is steeped in tradition and rich with history; this past year, it also became a home for innovative and community-based public art. By installing digital screens with poetry along hiking trails, shining brilliant lights on the façades of historic smokestacks, and creating kaleidoscopes of color in unexpected corners of the city, world-renowned artist Erwin Redl worked with neighborhoods to transform public spaces in ways that made “Sparkle City” shine.

Spartanburg was one of four winners in Bloomberg Philanthropies’ first Public Art Challenge—a competition that brought mayors and artists together to tackle their communities’ thorniest challenges. The art in Spartanburg was designed not only to be beautiful, but also to start conversations and foster closer relations between police officers and residents. The project would never have happened without the strong support of the local government, including the mayor and the police chief.

Spartanburg is a great example of the goal we set last year for all of our programs at Bloomberg Philanthropies: strengthening our efforts to assist governments around the world. Cities are at the center of this work because our mission is to ensure better, longer lives for the greatest number of people, and the majority of the world’s population live in cities. By 2050, some 70% will be urban dwellers.

We strongly believe that by enlisting and empowering mayors and local officials, we can multiply our impact. We have found that the most complex global challenges—whether fighting the causes of climate change, improving public health outcomes, or strengthening community-police relations—are often best approached with local solutions. It’s a strategy that has proven to be powerful time and again in cities like Spartanburg and around the world.

Our work focuses on five key areas: the arts, education, the environment, government innovation, and public health. In each program area, we seek challenges overlooked by others, and we work with partners to follow the data and advocate for proven solutions.

Over the past year, Bloomberg Philanthropies formed a number of new partnerships to advance our mission in new ways:

- Building on our partnership with Johns Hopkins University, we launched the $300 million Bloomberg American Health Initiative. Its goal is to find solutions to U.S. public health challenges through enhanced research, endowed professorships, and new academic programs, including a Doctorate in Public Health and a Master of Public Health fellowship. These efforts focus on fighting the challenges of drug addiction, obesity, gun violence, adolescent health problems, and environmental threats—all of which have contributed to the first decline in average American life expectancy since 1993.

- Furthering our support of mayors across the world, we formed a partnership with Harvard University to establish a new $32 million leadership training program. This collaboration to advance leadership, management, and innovation will equip mayors and their senior staff with the tools, skills, and support increasingly required to tackle the complex challenges faced in governing cities.

- Reflecting the deep impact that the institution had on Mike’s passion for science and problem-solving, we funded a $50 million endowment for the education center at the Museum of Science in Boston, naming it after his parents, William and Charlotte Bloomberg. This center will further the museum’s work of sparking lifelong curiosity about science—and, perhaps, even inspire the next Mike Bloomberg.

In addition to launching these new efforts, we made great progress in areas where we have already been hard at work:

- Over the past year, our long-term global initiative to curb tobacco use continued to bear fruit: cities in China, such as Shanghai and Shenzhen, fully implemented smoke-free laws with Bloomberg Philanthropies’ advice—helping to improve the lives of tens of millions. And in Uruguay, with our support, the government won a landmark international legal battle that involved protecting its tough anti-smoking efforts from interference by the tobacco industry. Additionally, we have seen a decline in global cigarette sales: 220 billion fewer cigarettes were sold in 2015 than in 2012. In the past ten years, our fight to reduce tobacco use has helped to save 30 million lives.

- After the proven success of taxes on sugary beverages in Mexico, Mike Bloomberg supported advocacy campaigns to spread similar policies in U.S. cities. As he noted in his letter (and it’s worth repeating): seven U.S. cities and counties have adopted soda taxes over the past two years.

- This past year, our work in more than 420 cities across the globe was strengthened. Bloomberg Associates, our international philanthropic consulting firm for city governments, provided deep expertise and advice to mayors and their teams, including to five new select cities. And our Government Innovation team’s Mayors Challenge ran its third regional competition, this time in Latin America and the Caribbean. The contest encourages cities to propose bold new solutions to urban challenges that improve city life and have the potential to spread to other cities around world. The 2016 grand prize winner, São Paulo, put forward an innovative approach to connect farmers to urban markets.

- Through our Women’s Economic Development program, we helped connect more female entrepreneurs to markets around the world: coffee grown and produced by partners in Rwanda is now sold at the Marriott hotel in the capital city of Kigali and will be served on RwandAir flights across Africa, Europe, and the Middle East.

- Furthering our fight to curb the effects of climate change, Bloomberg Philanthropies formed a partnership with the European Union to create the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy, uniting more than 7,400 cities from 121 countries in efforts to reduce carbon emissions and adapt to climate change. Through these cities’ public commitments and their collective actions, we are building a greener, more resilient future.

- Here at home in the United States, we expanded our work to support access to opportunity for all students: we grew CollegePoint, a college access program that uses technology to connect talented lower-income students with advisors. We have already reached more than 21,000 students. In addition, we built a growing coalition of almost 70 university presidents willing to work to increase the number of high-achieving, lower-income students who graduate from their schools. And in several cities across the country, we backed innovative pilot programs focused on career and technical education, collaborating with businesses to ensure that young people, even those who do not go to college, have the skills to get good jobs.

- Our fight for a cleaner, healthier America continued. The Beyond Coal campaign recently hit a major milestone. Our initial goal was to close a third of the 523 U.S. coal-fired power plants that were in operation when we began. Today, more than 250 coal-fired power plants have been retired or have committed to retire thanks to grassroots efforts across the country— far exceeding our goal. Beyond Coal has been called one of the most effective environmental campaigns in history.

- At Bloomberg L.P., employees advanced the company’s tradition of serving local communities. In 2016, more than 11,000 employees contributed over 128,000 volunteer hours in cities around the world.

Last year, Mike Bloomberg and I went to Mexico City for a meeting of city leaders who were showcasing ingenious ideas being implemented around the world. At a local school we visited, we saw children, no older than 10, drinking clean water from new drinking fountains. These fountains (as seen on the cover) had been recently installed using funds from Mexico’s sugary beverage tax, a law we supported. In that moment, I was reminded of the simplicity—and the power—of our work.

Finally, I have two recommendations for the year ahead: a book to read and a film to see. (Although, I have to admit, I am a little biased.)

Climate of Hope, written by Mike Bloomberg and Carl Pope, the former executive director of the Sierra Club, showcases the incredible work of local communities in combatting climate change around the world and points a hopeful way forward for us all. In addition, a new documentary, From the Ashes, looks at the future of coal in America and at what’s at stake for our economy, health, and climate. The film was directed by Michael Bonfiglio and produced by RadicalMedia in partnership with Bloomberg Philanthropies. With this book and film, we hope to broaden the conversation about practical solutions to fight climate change, enlisting people from all walks of life and from across the globe.

Thank you for taking the time to read and learn about our efforts, both new and long-standing, in this year’s annual report.